6 min read

Dec 22, 2025

Table of contents

01 Agents Require Forkable State02 A Shared Conclusion, Different Implementations: Replit and Tiger Data03 Engineering Tradeoffs and Workload Scope04 From Platform Internals to Shared InfrastructureReplit recently published a technical deep dive into the snapshotting infrastructure inside their agentic development platform. It’s always great (and educational) when tech companies provide such clarity and visibility about their internal infrastructure. In this case, Replit openly discusses storage design, copy-on-write semantics, and the systems challenges that arise once agents, not just humans, become first-class developers.

What also stood out to me, beyond the engineering, is the problem Replit explicitly names. Once agents are in the loop, iteration becomes the norm. Agents need to fork state, explore alternatives in parallel, and safely backtrack when an approach fails. Traditional database and storage systems, designed around linear production workflows and a small number of long-lived environments, make this kind of experimentation slow, costly, and risky. Replit is right to call this out as a fundamental mismatch between how agents work and how our infrastructure has historically been built.

I was also struck by how closely Replit’s conclusions align with our own vision for data infrastructure for agents, and the Fluid Storage architecture we announced a few months ago:

Fluid Storage: Forkable, Ephemeral, and Durable Infrastructure for the Age of Agents

At a high level, we arrived at the same answer. Once agents operate on real application state, databases must become forkable. And once databases are forkable, that capability has to be grounded in storage that supports fast branching, copy-on-write semantics, and scalable isolation. That convergence is not an accident. It reflects a deeper shift in how systems must behave when experimentation is central rather than incidental.

Traditional databases assume environments are few. Cloning is rare, snapshots are slow and expensive, and rollback is extremely uncommon.

Yet software development using agents diverges significantly from the traditional, linear human approach. Agents operate by branching, making errors, and retrying. The unit of iteration extends beyond git-backed code to full environments, as agents benefit from validating and testing changes against live services and production-like data, using any resulting errors as direct feedback. This shifts how databases must be treated; they must be inexpensive to duplicate, safe to roll back, and easy to discard.

This need persists into production. Production databases must remain performant and reliable, but they should also support fast, inexpensive forks for ongoing development and testing. Schema changes can be explored on forks and merged into production once finalized.

Both Replit and Tiger Data reached the same architectural conclusion: databases require native support for snapshots, copy-on-write semantics, and fast forking. This design fundamentally changes how development works: snapshots become safety boundaries, and forks become cheap and reversible, making experimentation a routine, painless part of the process.

And rather than modify the internals of the database, both Replit and Tiger Data looked at a natural system boundary for state—the block storage layer—and implemented these capabilities at the storage layer. And once storage is forkable, it becomes possible to build forkable databases (and other systems) on top. Each database or file system checkpoint defines a consistent point in time that can be forked from and restored to.

But there are some important differences, primarily due to the underlying storage substrate and the specific workloads each was designed to handle.

Replit's Bottomless Storage is built on Google Cloud Storage (akin to AWS S3 or Azure Blob Storage), using immutable 16 MB objects as the fundamental storage unit. At this layer, access is inherently slow—read latency ranges from 10s to 100 milliseconds—making direct object storage unsuitable for interactive applications.

To bridge this performance gap, Replit employs a three-tier architecture. Client VMs run btrfs as their local filesystem (tier 1), which communicates via the network block device protocol to dedicated "margarine" servers (tier 2) that manage the translation between filesystem blocks and GCS objects (tier 3). When a client requests a 4 KB block, margarine checks its local memory and disk cache; on a miss, it fetches the entire 16 MB block from GCS and caches it on local disk to serve subsequent requests. Write operations follow the inverse path: when btrfs commits a transaction, margarine detects the commit by monitoring super block writes and asynchronously writes dirty (written) 16 MB blocks back to GCS.

This storage was originally developed as the file system for agent sandboxes, which works particularly well when files are mostly immutable or where modifications are colocated, such as append-heavy logging workloads. Such scenarios reduce the inherent write amplification of such a design, where a single 4KB update can translate to a 16MB write to GCS. The architecture also performs well when an application’s working set is relatively small and colocated, allowing most reads to be served from the margarine servers’ local cache rather than repeatedly fetching large objects from object storage.

The same design becomes more challenging for workloads with fine-grained, random access patterns and large working sets, where frequent cache misses can force repeated 16 MB object fetches and increase latency. These tradeoffs reflect the underlying economics and semantics of object storage and help explain why this architecture is well suited to simpler, experimentation-focused environments.

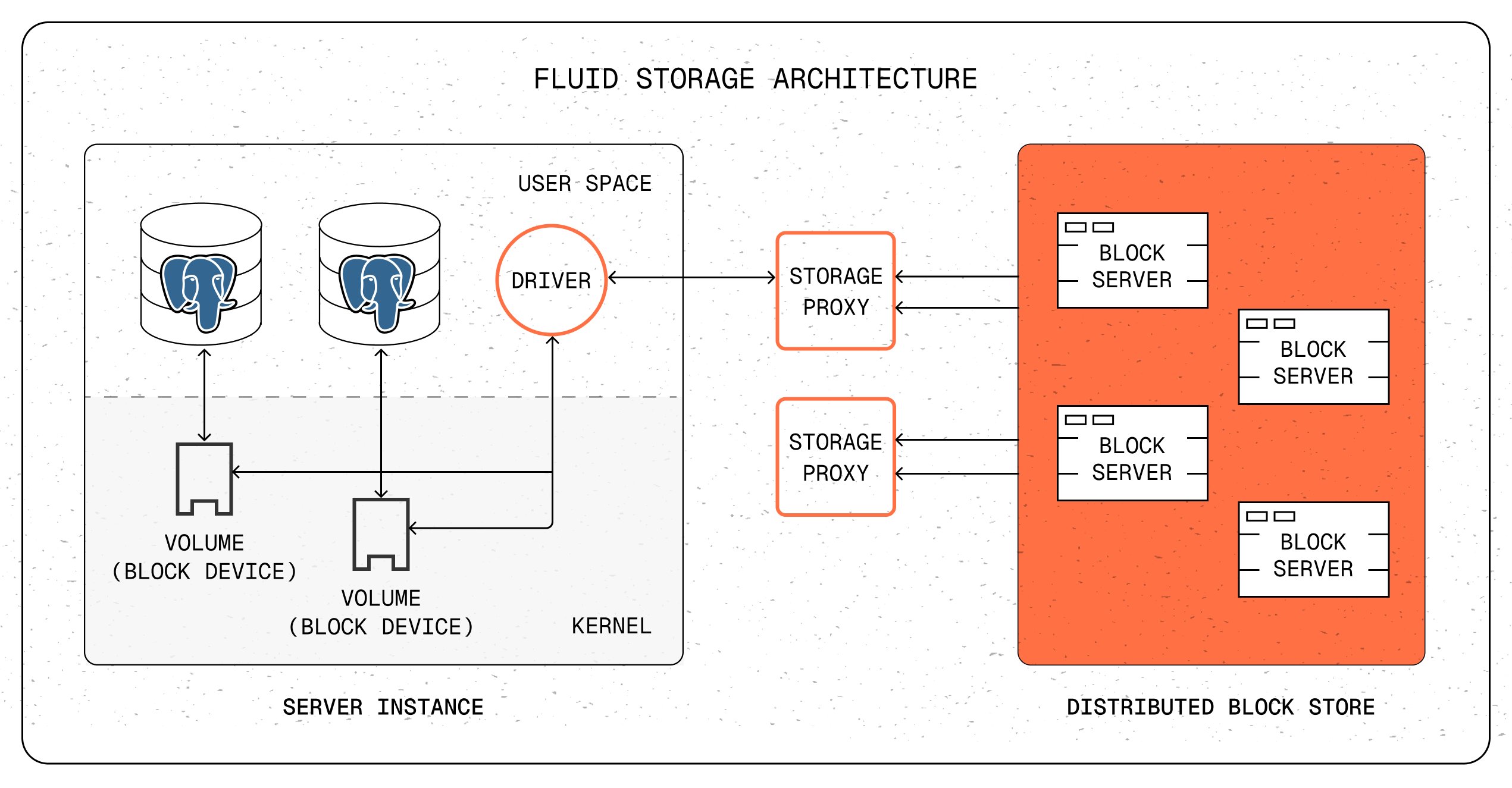

Fluid Storage is Tiger Data’s storage layer for forkable databases, built to support both agentic experimentation and operational workloads. At the top layer, and like Replit’s system, database compute nodes interact with Fluid Storage as a conventional block device (tier 1), issuing reads and writes for individual database pages. These requests are handled by Fluid Storage proxy nodes (tier 2), which manage volume metadata, snapshots, and routing, and forward block operations to the underlying distributed block storage layer (tier 3).

The lowest tier of Fluid Storage is still block-based. Rather than aggregating pages into large immutable objects like Replit, Fluid Storage persists individual 4 KB blocks directly. These blocks are stored on Tiger Data’s replicated storage layer, which provides durability, availability, and fault tolerance through its own synchronous replication protocols between storage nodes, rather than relying on an external object store. Reads and writes operate at block granularity, with typical read latencies on the order of a millisecond and write latencies under five milliseconds.

This design avoids the need to coalesce small updates into larger objects and eliminates the amplification effects that arise when fine-grained database access patterns are mapped onto coarse, immutable storage units. It also allows reliability and availability to be handled natively within the storage system, rather than delegated to an object store. As a result, Fluid Storage preserves predictable performance for transactional and random-access workloads, while still enabling fast, inexpensive database forks for experimentation, testing, and ongoing development against real data.

These architectural differences reflect different tradeoffs. Both systems respond to the same need of enabling fast, safe experimentation for agents, but they optimize for different points in the design space.

Replit’s decision to build on cloud object storage is a pragmatic tradeoff. Managed object stores like GCS are significantly cheaper on a per-GB basis than local NVMe storage, and they provide immediate durability and “bottomless” scaling. By anchoring their design on immutable 16 MB objects, Replit could move quickly and let the object store handle scaling and durability, rather than building and operating that layer themselves. For experimentation-first workloads with localized access patterns, the higher latency and coarser granularity can be effectively amortized through caching and batching.

Tiger Data made a different tradeoff. We invested in building fine-grained block storage from the ground up. That required more engineering effort at the storage layer, but preserved lower latency and much less read/write amplification across a range of workloads, while still supporting fast forking and cheap experimentation. As a result, Fluid Storage was designed to support the same experimental workflows Replit targets, while also serving sustained operational database workloads. The goal was not to trade experimentation for production, but to support both on the same infrastructure.

What struck me most in reading Replit’s deep dive was how closely the design goals, and even some of the high-level architectural choices, mirror what we built with Fluid Storage. Starting from different contexts, both systems converge on the same realization: once agentic development becomes the norm, infrastructure has to change. When experimentation is continuous and stateful, databases and storage can no longer assume linear workflows or infrequent cloning. Forkable state stops being a convenience and becomes a requirement.

One final key distinction is scope. Replit built snapshotting as an internal capability, tightly integrated with their platform. Tiger Data built Fluid Storage as shared data infrastructure, available to all customers and designed to support agentic experimentation alongside operational databases. Replit’s solution powers their platform, while Fluid Storage generalizes the capability for use across applications, environments, and production systems.

So teams building with AI or building agentic platforms do not need to build such infrastructure from scratch themselves. Fluid Storage is available today in Tiger Cloud, providing forkable databases as a foundation for experimentation, testing, and production systems built with agents in mind. Feedback welcome.

About the author

By Mike Freedman

Five Features of the Tiger CLI You Aren't Using (But Should)

Tiger CLI + MCP server: Let AI manage databases, fork instantly, search Postgres docs, and run queries—all from your coding assistant without context switching.

Read more

Receive the latest technical articles and release notes in your inbox.